Sometimes, when people believe things that probably aren’t true, other people die. Anti-vaccination rhetoric causes death by measles. Islamophobia kills refugees in the Mediterranean. Climate change denial may well destroy our planet and end human life as we know it.

The Bowling Green Massacre in the US, reports of Russians hitting Idlib terrorist warehouses, and stories about German soldiers assaulting teenagers exemplify the more insidious ways in which falsehoods can be weaponised. Flaws and biases in human reasoning can be exploited to turn countries and people against one another, undermining faith in democratic institutions, governments, elections, the media and civil society.

The internet, it seems, is making it easier to spread these kinds of ideas, and to get others to believe them. It’s not just an academic issue, but academic ideas can help us to understand where what’s happening, where we’re going wrong, and steps we might take towards remedying the problem. As someone writing their thesis about the ways in which people decide who and what to believe online, I’ve been trying to figure out how best to write about this for a while. This is the end result.

I want to talk about a few different things here. First, I want to question why you’re reading this at all. Why should you believe me? If we’re in the business of understanding why people read or believe some things or people rather than others, then it’s a good idea to start at home.

After that, we’re going to look at what’s new, and what’s not. The problems of “post-truth” and “alternative facts” are not new, and a lot of the reporting that suggests they are is sensationalist and unhelpful. But what is different about the internet? How does it change the ways in which we interact with knowledge, facts, data, and information? The problems haven’t really changed, but the media that we use alter the ways we encounter and navigate them.

Finally, we’re going to grapple with the problems facing experts trying to be heard online. Why can’t they communicate well? What’s the deal with “authenticity”? And how do you argue in a way that makes a difference?

I’ll be dropping in various ways in which we construct credibility and authority as we go. See those last three paragraphs? Those were signposting.

Why should you believe anything I say?

One of the only reasons that people are likely to read this or take seriously the things I’m saying is because I am a PhD researcher at a prestigious research institution. I also have a (relatively) shiny website filled with content curated to make me look like a Person Who Knows Things.

My chances of being read and believed could probably be improved if I hyper-specialised: got rid of the bits on the site about mental health and debating and academia more broadly construed, and slimmed the website down to a sleek set of pontifications on the concepts of expertise and authority, ideally limiting myself to the online arena. You would be less likely to believe me if my spelling or grammar were out of whack, or if this site were written entirely in Comic Sans, or if some of my other posts consisted of anti-Semitic screeds.

This kind of ultra-specificity is what we’ve come to expect from our experts: the more niche your topic area, and the less you deviate from it in your self-presentation as an author, the greater the likelihood that you’ll attract an audience. Moreover, it builds your Personal Brand as an academic/expert/authority/Thought Leader. It makes you more likely to get picked up by journalists who will propel you to expert status on a topic by dint of being seen on the set of the BBC with your name and credentials displayed underneath.

If you want to be listened to and called upon by “accepted authorities”, branding yourself as someone who knows about or does a particular thing is really important. Academic friends of mine (and others who are just academics – though it helps me to say that I have friends who are academics and whom people might have heard of) often do this in their Twitter handles: there’s The Lit Crit Guy, Early Modern John, Philosophy Bro, Philosophy Bites, Nuclear Anthro, and so on. Their names tell you what they do, like intellectual superheroes. In turn, that helps (in conjunction with a lot of hard work, raw talent and other kinds of skill and achievement) to develop a following on that particular subject. The brand matters a lot. I probably shouldn’t have called this blog timsquirrell.com, but I like to think I’ve got a silly enough name that people will forgive that particular slip.

Expertise, and the ability to be listened to and believed on a topic, is constructed rather than inherent. We believe people who have credentials, who specialise, who are already recognised as experts, who have endorsements from other already-recognised experts, and who present themselves as being free of biases and vested interests in a manner that is eloquent and engaging. None of these things tell us that a person is right about a particular thing or should be believed in a given instance, but they’re often the best indicators we have. It’s important for us to be aware of how they’re being used, regardless of the platform we’re on.

What’s new about the web?

The web’s form influences how we produce, consume and disseminate information. Those universal, indirect indicators of expertise I outlined above are remoulded and supplemented by the internet, its design and its affordances (the things that it allows you to do, which paths to doing those things it makes easiest, and the limitations it places on you).

This is true of any medium. We are beginning to come to terms with the problems that are exacerbated by the internet, but they are not new problems: people have always had to decide what to believe. And because the world is deeply complex and nobody has the time or other capacities required to learn everything directly by experience, what we believe in most domains will always be a function of who we believe. That in turn is influenced by a vast array of different factors, but it’s not something that is dictated by “logic” or “reason”.

So, what’s new about the internet? For a start, we’re going to be talking about two things that are separate but interlinked: the general affordances of the web, and the specific affordances of the platforms that exist on it.

General Affordances

1. Attention Economy

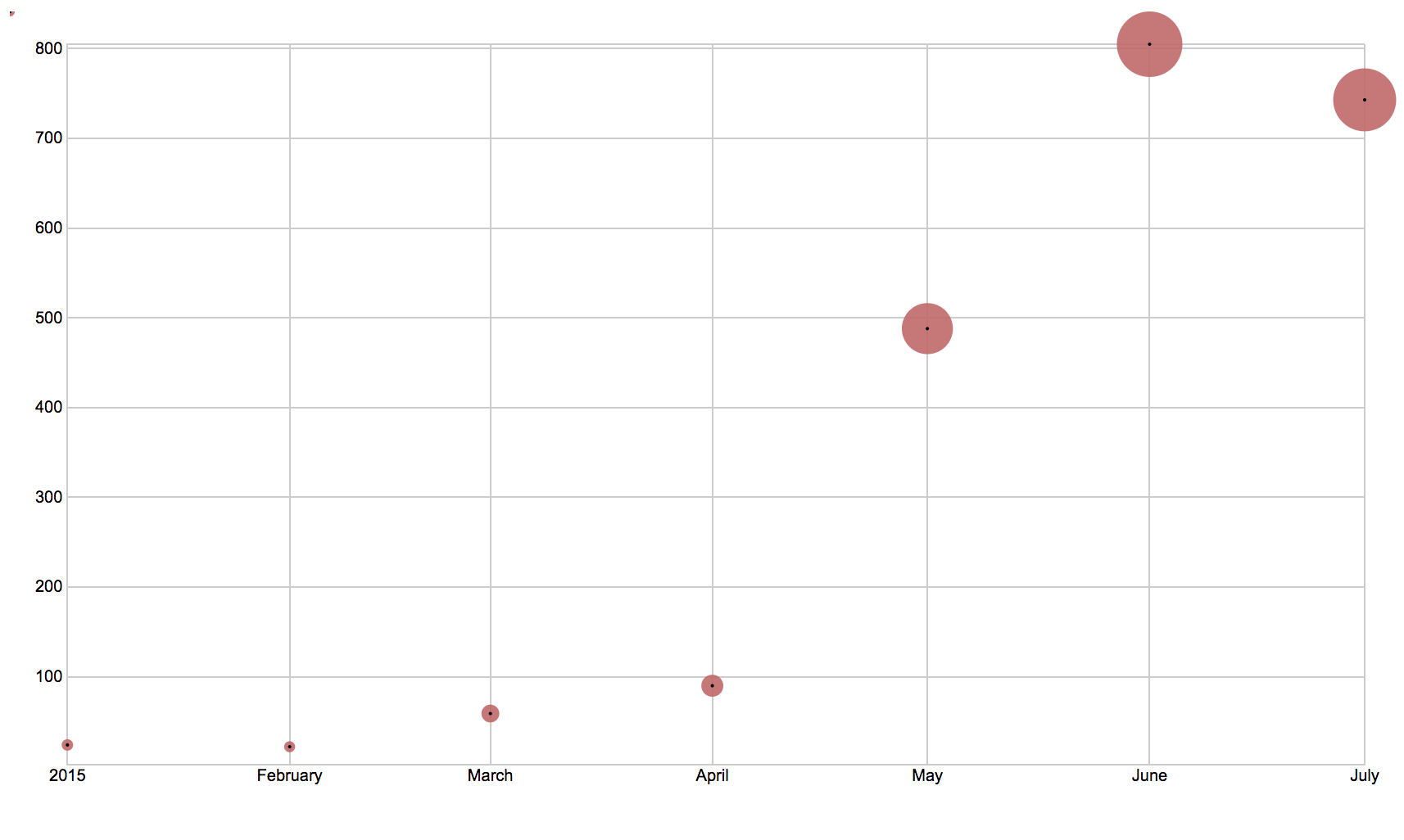

The internet is big. Really, really big. A site that I believed because it was one of the first results in my Google search told me that 500 hours of footage are uploaded to YouTube every single minute. 6000 tweets are made every second. Reddit has over 3 billion comments. We have to be discriminating about what we decide to attend to. Attention is the most important currency, and for us that’s important because it makes up half of the equation for belief. Belief is, essentially, exposure times credence. If you’re not exposed to something, it won’t shape your beliefs. In order to sway people, you first have to get them to see your content.

2. Hyperlinking

One of the key things that differentiates the internet from other media is that different places can link to one another. This does a few things. (1) It means that one author or website can recommend another by linking to it (think of the “blogrolls” you used to see on the sidebars of pre-Web 2.0 blogs), and drive traffic to that site. (2) It also plays a huge role in search engine algorithms, and given that search engines are the go-to for finding content, that makes hyperlinks important. (3) It means that people can use links to build their own credibility. If you’ve ever been in an argument on the internet, you’ll likely have encountered Those People who send you fifty different links that purport to back up their argument and then berate you for not reading them (as if you have time to read all of them and find exactly what they’re talking about before dissecting it in order to win a Facebook argument). Citations can be weapons.

3. Search engines

Search engines are the key way in which people tend to navigate the internet. That’s why search-engine optimisation (SEO) is such an important skill. Most people will never go beyond the first few results on Google, and their likelihood of going to the second page unless they’re a student trying not to get caught using the same sources as everyone else is practically nil. There’s a lot of speculation recently, for example, about the capacity of Google to influence elections purely by changing the order in which they rank search results. And the lack of realistic search engine competition (sorry, Bing) means that Google has a de facto monopoly on controlling what people click on when they look for things online.

Search engines also mean that people are able to instantly “fact-check” any statement. It might sound useful, but it’s treacherous: because we seem to have the capacity to check anything, we feel as though we’ve become empowered. We are the masters of our own beliefs, no longer beholden to experts telling us what to think. Doctors have come to dread patients coming in with print-outs and self-diagnoses from WebMD, and everyone’s little brother is now an expert on political theory because they read a couple of articles on Rational Wiki. But these two examples indicate the problem. We have the ability to search and find anything we want, but what we don’t have is the tacit knowledge – the know-how – to separate the good from the bad, and to figure out who and what is worth listening to.

4. Accessibility

For a long while, an area of intense scholarly focus was the “Digital Divide”: the idea that there was a separation between the kinds of demographics that go on the internet and the kind that do not. Those who were online were young, wealthy, white, western and so on. Whilst it is still the case that the majority of the world does not have access to the internet, access has become far more widespread in recent years. The panicked messages I received from my friend after their granny commented on my Facebook status, and the popularity of the subreddit “Old People Facebook”, would also seem to indicate that there is less of an age divide than there used to be. Pretty much anyone can make a website and get their voice out there.

The idea of the internet as a great leveller between elites and publics was predicated in part on this accessibility: anyone could put their views online, and the most articulate and interesting and logical would attract the most readers. Ha.

However, whilst you’re unlikely to be able to get your site to the front page of Google for any decent number of searches, you can still gain a sizeable following, no matter how niche your subject of interest. That means that researchers are able to put their material out there for a wider audience, and independent film makers can make really weird content like that horrible deep web video I watched with a man crying whilst eating soup. However, it also means that the kinds of people who used to write racist pamphlets now have websites, and they’re able to burnish their credentials in all kinds of ways (listing their subjects of expertise and the different places their writing has been featured, writing testimonials for themselves, and doing a lot of the other things that I’ve done on other pages on this site).

There are a number of other things that the internet changes (enough to fill a lot of books), but those listed above are probably enough to give you some idea of how our propensity to believe some things or people over others might be shaped by the medium we find ourselves using.

Specific Affordances

Let’s move on to specific affordances. These are the features of individual sites that influence our habits and behaviours. Because there are so many platforms, and they each have so many features to unpack, I’ll only cover them briefly here.

1. Facebook

(1) Facebook has a hidden algorithm that influences what content you are shown. This tends to skew towards content that is like that which you have previously clicked, reacted to or otherwise engaged with. As such, it tends to reinforce our beliefs to some extent. This is also true of groups that tend to collect like-minded people. See, for example, “Leftbook”. (2) There’s a strong skew towards recency. That shapes the kinds of things you’re likely to be talking about, so you’re probably seeing things based on how recent they are and how salient Facebook thinks they are to you, rather than based on their quality alone. (3) You primarily see things that have been posted by those you are friends with, and so there’s a skew towards being shown and interacting with those that you have met and spent time with. (4) The like/react functions tend to be self-reinforcing. When you’re reading through a Facebook argument which is 100 comments long, you’re likely to primarily read those comments that have been most liked already as an indicator of quality, and from there you’re more likely to pile on and like those comments. People who are good at writing things that garner a lot of likes from the first people to read them are more likely to have their opinions seen and given credence by others later on. (5) Facebook’s governance structure is quite pro-“free speech”. A recent Guardian exposé of the Facebook moderation regime showed that moderators were instructed to allow through the net a lot of content that many people would find objectionable. Shocking or graphic content that is allowed on Facebook often becomes highly viewed as a result of the ease of sharing content on your own timeline.

2. Twitter

This is a platform designed in such a way that it is almost impossible to change others’ minds. Why? (1) The 140 character limit means that disagreements are famously confrontational: it lends itself to bon mots, reaction GIFs, snippy one-liners and insults more than discursive engagement. (2) The follower system means that you’re highly unlikely to be exposed to dissenting opinions unless you actively seek them out or someone you follow retweets them with a disparaging comment attached. (3) Changing someone’s mind usually means engaging with their core beliefs, rather than specific examples. So when alt-right commentator Paul Joseph Watson gets “schooled” by a historian on ethnic diversity in the Roman Empire, the core tenet of his argument (that political correctness has gone mad and is rampant in state institutions) hasn’t been challenged; rather, he might have been proven wrong on just one instantiation of that principle. (4) Any attempt to engage at deeper levels requires users to thread their tweets together, or link to longer pieces on other platforms. Twitter has a very low click-through rate to external sources, rendering this pretty ineffective.

The upshot of this is that Twitter has a tendency to reinforce pre-existing beliefs rather than challenge them in any meaningful way. Inside groups who share beliefs, those who have the most followers are likely to be taken the most seriously. That tends to privilege those with social status elsewhere, or those who are particularly good at manipulating the constraints of the medium to produce wit and humour within 140 characters, rather than, say, those who are best able to articulate arguments.

3. Reddit

For a full exposition of Reddit’s functionality and the way that its design influences its users, it’s worth checking out the work of Adrienne Massanari, who is thus far the only academic to have written a book about the site. Her recent paper on GamerGate and The Fappening is enlightening: it argues that Reddit’s design, algorithm and platform politics support the creation of “toxic technocultures”. How so? (1) It’s very easy to create an anonymous account and a subreddit, so barriers to participation are low. It took me about 2 minutes to make /r/Ivory_Tower. (2) Reddit’s “karma” system works in such a way that opinions which are popular with site viewers (who tend to be young, white, male, geeky/nerdy, Western, and reasonably educated) are the most visible on the site because they get upvoted the most; moreover, karma becomes a signifier of social standing (in the same way as points do in other gamified environments) and this further incentivises posting in such a way that lurkers on the site are likely to agree with you. (3) Reddit has a very loose governance structure. Administrators refuse to ban communities or users for anything less than flagrant violation of the few rules that reddit has (for example, against doxxing, inciting violence, spamming, revenge porn, and a few other things that are either illegal or on the borderline). There are a number of communities which operate in a grey area where they are de facto breaking the rules, but with enough plausible deniability that they don’t get banned (e.g. KotakuInAction, home of GamerGate, and The_Donald, home of Trump’s fanbase).

What’s going wrong, and how do we fix it?

The key takeaway from the above is that the medium on which we communicate influences the messages we’re able to send and how they’re received. When we think about why people come to and maintain certain belief systems, we have to think about the platforms on which they’re consuming information. They might be searching the web for themselves, but blindly reading PubMed abstracts to understand nutrition isn’t helpful unless you understand how to read a scientific paper, and you’re systematic about which ones you read.

With these issues in mind, we can have a slightly more focussed discussion about what the specific problems are right now. I want to talk about three main things: the difficulty of communicating science and other academic-type information, the importance of authenticity online, and the difficulty of tackling core beliefs.

Communication

In science and academia, there are high premiums placed upon the ability to communicate your research to wide audiences, but how to do so effectively is still seen as fairly mysterious. Getting an article into a mainstream newspaper or onto a big site is lauded as an excellent achievement, but it tends to be a fairly small subset of people who do so consistently.

Social media is simultaneously seen as an important way to raise your profile, and also a waste of time that might make it difficult for you to find jobs in the future if you’re too outspoken. Most of the high-up researchers I know have very little social media presence, and without that they’re less likely to be approached by journalists (who are very engaged with Twitter in particular) asking them to engage with issues on a larger stage. Given that exposure is necessary to be believed, it probably behoves academics who are frustrated with the prevalence of “alternative facts” to cultivate a social media presence such that they can expose a wider audience to their thoughts.

The way in which research is presented in journal articles and conferences is often incomprehensible to all but those in the same field. That means that being heard and being believed by others necessitates writing and speaking in ways that are more accessible. In order to do that, you have to ditch some of the scholarly jargon and instead talk in terms that people understand. Our facility with technical language is helpful in academic contexts, but when you’re arguing with Brendan O’Neill on Radio 4, or trying to engage with the latest Alt-Right mouthpiece on Reddit, what matters more than academic precision is eloquence and the ability to articulate your ideas in a way that is rhetorically appealing.

It’s also important to learn to communicate within the restrictions of the medium. If you’re saying something on twitter, and someone else is saying the opposite, the tweet that is more likely to get picked up and believed is the one by the person with more followers, and the one that is more snappily written. Facebook privileges visual content over text, so you’re always going to get dwarfed by Britain First if you’re writing long-form Facebook Notes. If you post something to Reddit, you have to bear in mind that votes dictate visibility, and votes are weighted logarithmically, so the first ten count as much as the next one hundred in visibility terms. On YouTube, asking your audience to “Like, Comment and Subscribe!” is actually a vital prompt to push up the visibility of your videos, because each of those functions counts for a lot more than a simple view does. Your academic blog is much more likely to get hits from outside of your discipline if you use SEO techniques: link to other places and get them to link to you, make sure that your description texts have relevant keywords in them, and share it wherever you can.

The other thing to bear in mind is that often the people you want to persuade just aren’t the same people using the platform you’re on. Twitter, for example, is disproportionately populated by young people, journalists, politically active people and so on. Whilst your tweets might get picked up by Buzzfeed and peddled out to a wider audience, tweeting in and of itself doesn’t necessarily reach anyone but people who are likely to agree with you in the first instance (especially because engaging with people who disagree with you on twitter is the discursive equivalent of stick your face in a wasps’ nest). The successful dissemination of information is still primarily dictated by your social network. My most successful piece in quite some time, a guide to writing undergraduate essays, only ended up in the Guardian because a journalist Facebook friend of mine saw it on my Facebook and mentioned it to her journalist friend, who happened to be doing a piece of undergraduate essay writing. Branching out to platforms and outlets that you haven’t previously used is a fantastic way of reaching new audiences, but you have to make sure you frame your pitches and pieces in such a way that they appeal to that audience. Be aware of the demographics who read particular sites, the kinds of things they value, and what turns them off.

Some of the best examples of effective communication are in the natural sciences. Neil DeGrasse Tyson is a master of using multiple mediums to reach bigger audiences, appealing to the geeks of reddit, the jokesters of Twitter, and a public that loves to be wonderstruck by the universe’s majesty. Richard Dawkins, for all his flaws, is very good at putting across his views in a persuasive way both in person and over Twitter, whether we like to admit it or not.

YouTube has exemplary communicators: Minute Physics, CGP Grey, and Vox are all doing it right, taking advantage of the affordances of the medium to produce content that’s shareable. On Facebook, it’s important to put closed captions on your videos so that people can view them without sound whilst they’re scrolling their feed. Vox does that.

In the podcast world, Nigel Warburton and David Edmonds’ Philosophy Bites and Philosophy 24/7 are excellent examples of good marketing and branding that gets exposure: reasonably short interviews with highly-regarded academics on specific, engaging topics.

What these all have in common is that they recognise the audience that they are going for, they have strong branding, and they turn the medium to their advantage. On the other side of the political spectrum, the Alt-Right are doing the same thing. Rebel Media, pre-downfall Milo Yiannopoulos, and Donald Trump give masterclasses in how to utilise the affordances of web platforms to your advantage. Milo, for example, used the 140-character restriction of Twitter as an outlet for withering put-downs and provocations, rallying anonymous followers around him and recognising that it was a medium designed for confrontation, not persuasion. They all take advantage of the recency biases of most platforms by consistently churning out content, engaging and energising their audiences and making sure they are never forgotten. I hate to say it, but academics could benefit from taking a leaf out of the alt-right’s book.

Authenticity

The issue with social media and the constant exposition of large chunks of our lives to the scrutiny of others is that it means that nothing is forgotten, and maintaining a coherent self-presentation is incredibly difficult. It used to be the case that we could partition off different presentations of our selves for different contexts, such that the professional and the personal would never mix. Social media changes this, creating what danah boyd calls “context collapse”: you’re talking to everyone at once, whether you know it or not. That means you have to present yourself in such a way that you can talk to everyone at once without compromising the integrity of the narrative you’ve created about yourself for any given audience. It’s why people get scared about adding their family or colleagues on Facebook: they know a different version of you to the version that your friends know.

Because it’s practically impossible to maintain narrative coherence in your self-presentation, that makes an appearance of authenticity vital. Politicians do incredibly badly on Twitter when they’re seen as inauthentic, and they do very well when they’re seen as authentic: think post-2015 Ed Miliband, or Ruth Davidson, or even Donald Trump. Likewise, celebrities who do AMAs on Reddit are most successful when they’re seen as authentic, revealing themselves without the facade of screens and scripts and editing – Bill Gates would be a great example here, Woody Harrelson would be a terrible one. If you carve out a self-image of authenticity, then it’s easier to take the blows that inevitably come with using the internet, because you can hold up your hands when you’ve done wrong and admit it. This is part of why it’s becoming easier for politicians to admit to things like smoking weed, or using poppers – it’s not just because those things are becoming more acceptable, but because everyone has to be prepared to have their “embarrassing” secrets made public, and we are more forgiving of the mistakes of people who admit to them, or own them, as a result of that.

Large chunks of the establishment – politicians, more mainstream journalists, scientists and academics and lawyers and so on – have real trouble presenting themselves as authentic online, and that makes it harder for them to connect with people. That means they are less likely to be engaged with, and consequently less likely to be believed or given credence. It doesn’t matter that Milo spouts nonsense that he manages to pass off as social theory. He’s believed over stuffy leftie academics because he engages with his fans in a way that tells them he is authentic, that he cares about them and can relate to them. Crucially, he relays his ideas in ordinary language that’s accessible and often (arguably) funny.

Core beliefs

I think probably one of the key problems associated with arguing on the internet is that nobody wins. And I don’t mean that in the “ha ha, you’re all silly for arguing on the internet, what a waste of time, you’re all as bad as each other”, way. I mean that when you argue online, you’re primarily engaging over specific pieces of content or small things. If you imagine beliefs as trees, then the core belief (say, Islamophobia) is the trunk, the key concepts are the branches (Muslims are terrorists, Islam is taking over Europe, Muslims want Sharia Law in the UK/US/Australia/wherever), and the single news stories are the leaves. Those news stories are, more often than not, what we’re arguing over. Refuting the factual accuracy of some story in Breitbart does precisely nothing to take down the trunk of the tree, or even the branch. Questioning the credibility of Breitbart itself might help a bit, insofar as it’s an outlet that produces a lot of leaves, but it still doesn’t shake the core beliefs themselves.

A lot of internet platforms have a bias towards recency, using algorithms or other means to show us the things happening right now. That means we tend to be arguing over the news stories of the day, rather than necessarily the biggest/most important things. Because of that, we’re more often than not arguing over the shade of a particular leaf, or whether some branch might be rotten (I’m so sorry for this metaphor), rather than whether the tree itself could perhaps be cut down. That’s a real issue when it comes to trying to prevent the propagation of beliefs that we might consider to be actively harmful, like anti-vax or climate skepticism or anti-Semitism. When you just engage with the data given, you’re not attacking the core issues: things like distrust of establishment institutions, which is often caused by other forms of disenfranchisement or simply a failure to explain why those institutions merit trust.

The way to combat this is to engage with the trunk of the tree. A good example here is Vox: they produce videos that are short, but which manage to take a relevant recent news story and spin it into something that informs a broader idea or argument. Their videos on the South China Sea and the rise of ISIS are great examples of the purely educational, but their takes on the Trump administration are wonderfully shareable bits which highlight and analyse the central issues created by this government, rather than just reporting on a particular story.

Conclusions

As well as the specific suggestions above, I have a few tentative, broad-stroke suggestions for the direction we should take to resolve some of these issues. I think it’s incredibly important to educate our educators in such a way that they’re able to engage effectively, using accessible language and eloquence and rhetoric and analytical rigour. I think that we need to have a serious think about the ways in which the platforms we use might encourage or discourage critical thought and engagement. I think that scientists and academics need to be encouraged and given the tools to build social media profiles that will allow them to reach wider audiences and be heard over others who might claim to be experts (and who are always going to be ready and willing to speak, no matter they lack of qualification). But the main thing I’m trying to do with this piece is to gently nudge people in the direction of thinking about how the platforms we use shape the kinds of discussions we have, and how those discussions influence our beliefs. We’ve always been living in a post-truth world, but we’re more aware of it now. To turn that to our advantage, we have to understand how it operates. This is the first step on that journey.